Lupus is a lifelong disease that can lead to serious complications over time if left untreated – including irreversible organ damage – but many patients remain in the dark about the risks. Thankfully, scientific innovations in immunology mean the menu of treatment options has expanded to help change the course of the disease – and, ultimately, prevent organ damage from occurring.

During Isha’s first semester at university in Boston, US, she couldn’t shake the symptoms of what she thought was a bad viral infection: she kept getting a fever, suffered from extreme fatigue and felt unable to function as normal.

Things weren’t getting any better by Spring Break, and when Isha saw a doctor about it, he sent her to hospital. After weeks of testing, the mystery was solved: she had systemic lupus erythematosus, more commonly known as lupus.

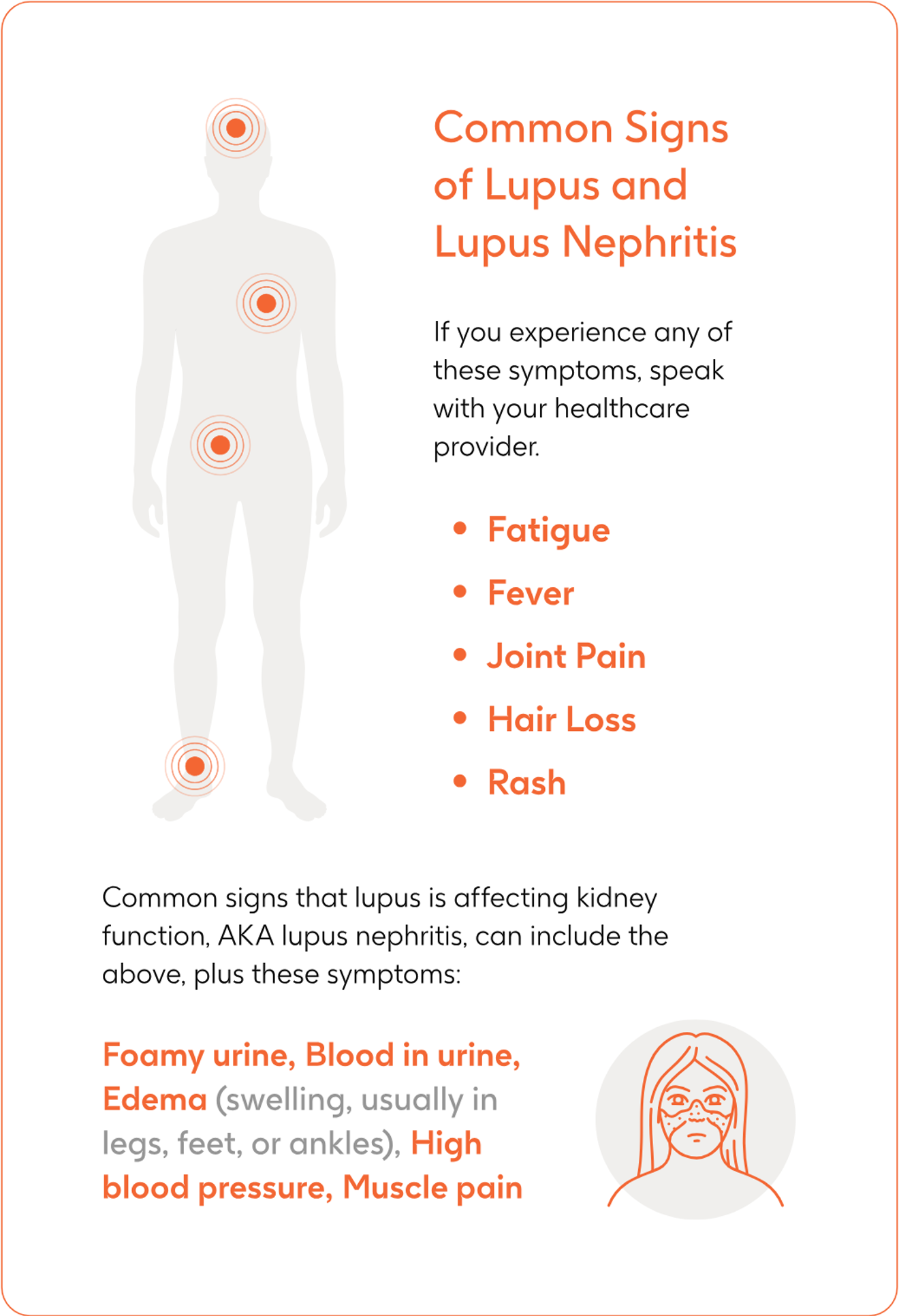

Isha, who was diagnosed in 2016, is among the estimated 5 million people globally living with lupus – a disease where the body’s immune system mistakenly attacks healthy tissue. Symptoms vary widely, making it difficult to identify and, in many cases, it can take years to diagnose. The most common signs include pain and swelling in the joints, skin rashes, fever, hair loss and anaemia.

While diagnosis often comes as a relief to those living with lupus, it is only the beginning of a lifelong journey of coping with the disease.

“My management for lupus initially was a bit rocky,” says Isha. “It was such a trial-and-error situation. I remember my doctor telling me, ‘You need to listen to your body, you need to understand your body really well and keep a lookout for symptoms.’”

Lupus patients suffer periods where their symptoms worsen, known as flares, even while they are receiving treatment. These episodes can last for days, weeks, or longer, and can be very disruptive, even leading to hospitalisation in severe cases.

Flares can also be detrimental to a patient’s long-term health, because they increase the risk of organ damage, which occurs in an estimated 30% to 50% of lupus patients five years of diagnosis.

What can make lupus difficult to treat is that can strike many parts of the body, but it is particularly dangerous when it occurs in the kidneys. This inflammatory injury to the kidneys, a condition known as ‘lupus nephritis’, can develop without any obvious symptoms at first, before presenting in a patient as swollen hands, feet and ankles, brown and frothy urine, puffiness around the eyes and stomach, and fatigue.

In the most serious cases, it can lead to end-stage kidney disease, requiring dialysis and transplant.

‘Surprise and confusion’

Isha was diagnosed with lupus nephritis after her symptoms got worse and led to her being hospitalised a year later. Her diagnosis came as a shock because her doctors had not raised the possibility of organs being impacted by lupus, and some medicines used to treat it, until it was too late.

Isha’s kidney injury had progressed to an advanced stage in which more than half of her kidneys had been affected, otherwise known as lupus nephritis class 4.

“When I first realised that I had lupus nephritis, it was surprise and confusion,” Isha says on how it felt to receive the new diagnosis.

“Like how could that be, how is that possible, and how do things get here?

“It was strange that organ damage is not something that was talked about [with my doctors], not something I was warned about, not something that was discussed at all until I was experiencing it, until I actually had a kidney biopsy, and I was diagnosed with nephritis class 4.

“If my doctor had warned me about these we could have saved a lot of time and energy and money and just emotional stress. I think it’s very important to have those conversations.”

Unfortunately, Isha’s experience is not unusual. A global GSK survey released in 2022 found that nearly half of doctors waited to discuss the risk of organ damage associated with lupus until after their patients came to them with symptoms.

“Organ damage is almost always irreversible,” Dr Karen Costenbader, Director of Lupus at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, says.

“You must discuss it upfront. Even if the patient is feeling OK, you have to talk about those risks.”

High-dose steroids

In another complex twist for lupus patients, organ damage can also appear due to high cumulative doses of corticosteroids, the most common treatment for lupus flare ups.

Corticosteroids work by suppressing the immune system and reducing the inflammation that drives lupus flares in different parts of the body. But the use of corticosteroids can have harmful short-term side effects, like infections.

Long term use can also cause irreversible organ damage, because as well as treating inflammation, steroids also impact healthy parts of the body.

Irreversible organ damage can occur in about 40% lupus nephritis patients after five years of being diagnosed and undergoing long-term steroid treatment. When it happens, it can deeply affect a patient’s quality of life, affecting their cognition, their ability to procreate, causing them pain, poor body image, and emotional health issues. It is also related to an increase to the risk of further organ damage and early mortality.

“The initial dose that my doctor prescribed for the steroids was pretty high at the time, and I was on that dose for quite a while,” says Isha.

“My symptoms as a result of that were weight gain, feeling very hungry, my face swelled up and I had a lot of water retention.”

“One reason that patients stay on steroids for longer than they should despite the risks is that the relief from the symptoms of lupus is instant,” says Dr Costenbader.

“If people have a lot of systemic manifestations of lupus at the outset, they feel better [on steroids] and don’t want to come off.

“It’s that push to get them off as the longer-term medications kick in. You’ve got to keep repeating that these [steroids] can increase your risk of weight gain, heart disease and osteoporosis, to name just a few.”

Early prevention

The good news is that steroids are not the only medicines available to control lupus flare-ups. Through years of research, scientists have developed greater understanding of the disease and created disease modifying treatment options.

Targeted medicines work in a more precise way, blocking specific parts of the immune pathway that trigger symptoms, tackling the cause of inflammation rather than just alleviating the symptoms. These treatments have been shown to reduce the frequency of flares, need for continuous steroids and the organ damage associated with them.

These medicines do not cure lupus, but there is strong evidence to suggest that they change the trajectory of the disease by preventing or delaying irreversible organ damage like end-stage kidney disease.

The greatest benefits to patients, however, come from earlier intervention with precision treatments.

“We like to use the term ‘window of opportunity’ to avoid the damage caused by the disease,” says Roger A. Levy, Senior Global Medical Director in Rheumatology and Specialty Medicine at GSK.

“The patient that was treated without damage is more likely to have the benefit. Those that are controlled at the early stages, before there is damage, and are kept under control, may require less steroids and a reduced risk of damage accrual. It is important that HCPs and patients are aware of this and that they align on a treatment plan for the long-term.”

Research to better understand which lupus patients are at greatest risk of damage to particular organs through genetic testing is also underway.

"Our focus is to help patients feel better today, tomorrow, and for generations to come,” Dr Levy concludes.

“We’ve made significant advancements in the field of lupus research and continue to do so, such as identifying key mechanisms that can help to modify the course of disease.

“In addition to advancing the science and treatments for patients, we also continue our strong partnership with the entire lupus community to make sure their voice is heard and part of the work we are doing.

“And this is all just the tip of the iceberg of how we will continue to improve the lives of lupus patients.”