Scientific advances have helped reduce meningitis rates across the world – but the need for awareness and innovation regarding prevention strategies continues. Here, one teenage patient tells her story – and what she wants others like her to know about the disease.

Meningitis occurs when the membranes that surround and protect the brain and spinal cord become inflamed. This inflammation can have many different causes but two of the most common are viruses and bacteria.

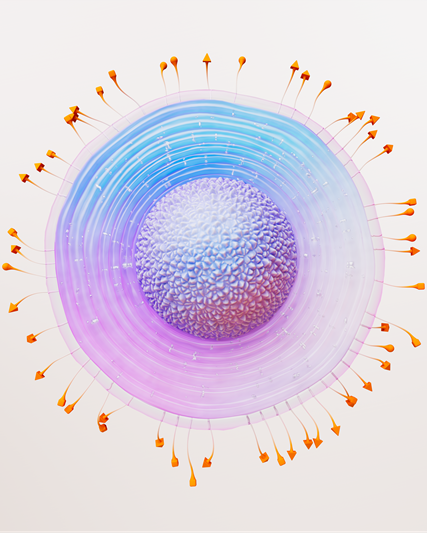

Around 1 in 10 of us carry the most common cause of bacterial meningitis, Neisseria meningitidis, in our nose and throat. However, it’s only when these bacteria break through the throat lining and enter our bloodstream that they cause harm, leading to a disease called invasive meningococcal disease (IMD).

Instances of this ‘break-through’ are relatively unusual, yet despite this, IMD still affects around 1.2 million people around the world each year.

IMD can progress rapidly. In around 1 in 6 cases the disease can cause death, sometimes in as little as 24 hours. The most common symptoms include fever, headache and a stiff neck which can be accompanied by nausea, vomiting, sensitivity to light and confusion.

The disease can affect any age group, but babies and young children are particularly at risk, as their bodies’ immune systems are not fully developed. Adolescents and young adults are also at risk, particularly at key life stages like starting college or university.

A post-Covid pandemic rebound in the number of IMD cases among teenagers has caused concern among healthcare bodies and experts across the world. As people began mixing again after the Covid-19 pandemic, IMD cases rose, including amongst adolescents in the UK, France and New Zealand.

“We saw that the social distancing measures used to limit the transmission of Covid-19 had an impact on all infectious diseases spread by airborne transmission,” Professor Chiara Azzari, who works in the department of pediatrics at the Anna Meyer Children's Hospital and at the University of Florence in Italy, says.

“However, the bacteria didn’t go away, so when the social distancing measures were relaxed, the bacteria resumed their circulation. It’s no surprise that once we all started mixing again, these diseases started spreading again with spikes in meningitis recorded.”

“Rates of invasive meningococcal disease have declined substantially since a new preventive strategy was introduced 10 years ago,” says Phil Dormitzer, Global Head of Vaccines Research and Development at GSK. “But we can’t be complacent. We need to keep progressing the science and work with healthcare professionals and the public to improve accessibility to preventive tools for the target population susceptible to meningococcal disease.”

‘It hit me like a ton of bricks’

Kate was 16 when she contracted IMD while working as a camp councillor in Nova Scotia, Canada.

“A couple of days after I’d gotten back from camp, I woke up one morning feeling rundown and unwell,” she says.

“It’s not unusual to get ill after being run ragged all summer, so I put it down to post-camp exhaustion and thought I’d just lay down for the day. Fast-forward 12 hours and I wasn’t feeling any better and had started to get purple spots on my legs. At that point my parents made the decision to drive me to the hospital – no mean feat in rural Canada!

“When I first arrived at the hospital I was presenting with symptoms like the flu. It wasn’t until I was in the back of an ambulance being taken to a much larger hospital that the tell-tale symptoms of meningitis hit me like a ton of bricks, and I started to get a sore neck and headache.”

Recognising the symptoms of IMD – like a stiff neck, fever, and a headache – may help ensure swift treatment and increase a person’s chances of survival. In Kate’s case, this might have been the difference between life and death.

Even so, she spent the next week in an induced coma. The Neisseria meningitidis bacteria in her blood were multiplying, releasing poisonous chemicals called endotoxins which overcome the body’s natural defences. Meanwhile, these toxic chemicals were damaging Kate’s blood vessels, causing them to haemorrhage and damaging her internal organs.

IMD symptoms

The most common symptoms include:

- Fever

- Headache

- Stiff neck

There are often additional symptoms, such as:

- Nausea

- Vomiting

- Photophobia (eyes being more sensitive to light)

- Altered mental status (confusion)

In the later stages, damage to the walls of the blood vessels can also cause a rash of red/purple spots or bruises that do not fade under pressure.

Newborns and babies may not have the classic symptoms listed above. Instead, babies may be slow or inactive, irritable, vomiting, feeding poorly, or have a bulging anterior fontanelle (the soft spot of the skull).

Thanks to the treatment she received, Kate survived. She spent around a month in the hospital, focusing on her recovery and re-learning to walk. She then spent several months at home regaining her strength and managing her wound care for the many scars left by the damage the disease had done to her blood vessels. She also attended various specialist appointments and underwent surgery to remove a part of her toe.

Professor Azzari has seen firsthand the immediate and longer-term impact that IMD can have.

“The first hours after the infection are the most crucial, and some infected patients do not survive longer than a couple of days. For those who survive, permanent damage like hearing loss, seizures, visual impairment, co-ordination problems, and psychological issues can be experienced. Septicaemia, an added complication, can also cause skin damage and scarring, amputations, and damage to lung, liver, and kidneys.”

Significant progress

Luckily, Kate made a full recovery. She now works with charities across Canada to raise awareness of the risks of IMD.

She especially wants to help increase awareness among teenagers setting off for camps, college or university.

“Our teenage years are such an exciting time. We’re becoming our own person, heading off away from home, and while we may feel invincible – we’re actually at high risk of meningitis.”

It’s precisely these life-changing moments that can increase a teenager’s risk of contracting IMD. The Neisseria meningitidis bacteria can spread more easily in crowded places like dorm rooms or assembly halls via coughs and sneezes. Fortunately, innovation in science has given us ways to help prevent the most common strains of the bacteria from causing so much damage.

Scientists at GSK continue to study Neisseria meningitidis, constantly evolving tools to help prevent infection. As a global leader in meningococcal prevention, GSK’s research and development efforts focus on simplifying meningitis prevention, helping to protect those age groups most at risk.

“Significant steps have been made in the last 30 years and the incidence of bacterial meningitis and sepsis has significantly decreased in some regions,” Professor Azzari continues.

“However, the pace of innovation must continue to ensure we can protect children, adolescents, and young adults – for whom invasive bacterial infections are still a significant cause of hospitalisation and death.”

In the future, Kate hopes that scientific research combined with increased awareness will mean that people are able to prevent or effectively treat most cases of IMD.

“One day I hope I won’t have to talk about meningitis anymore, because everyone will know about the risks and how to protect themselves.

“Until then, I know there’s power in me sharing my story. If just one person recognises their symptoms because of it, I’ll be happy.”